How Yale Monitors COVID-19 Surges in Connecticut's Wastewater

Predicting Outbreaks Before They Happen

Pandemics present a unique civic challenge for public health officials. How do you monitor infection levels in large groups of people who are very close together in a repeatable way, using limited labor and reagents?

The answer lies beneath our feet. Sewers carry the viral components shed by infected individuals to wastewater treatment plants, where those components settle with solid waste into an unsavory but informative component: sludge.

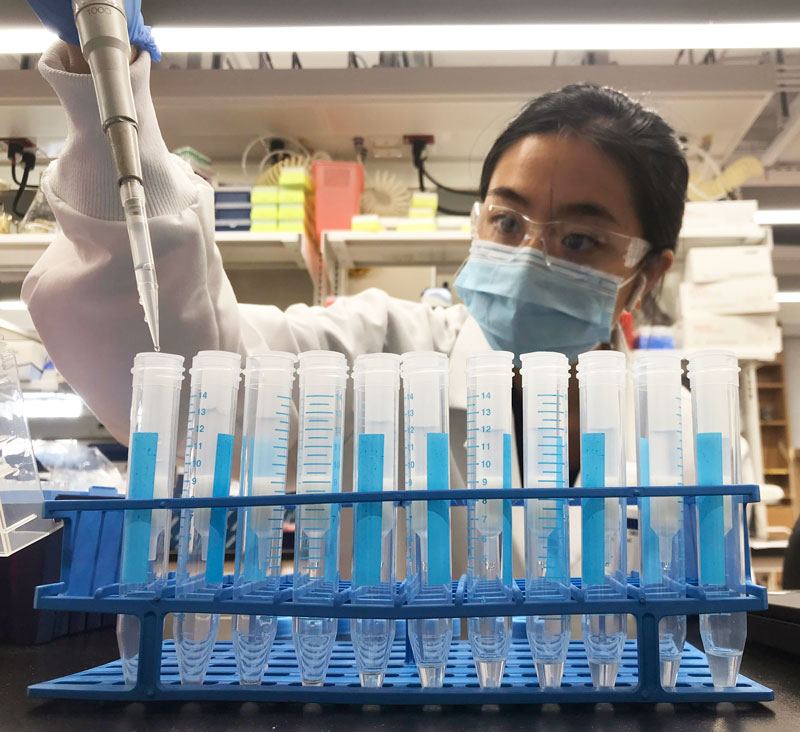

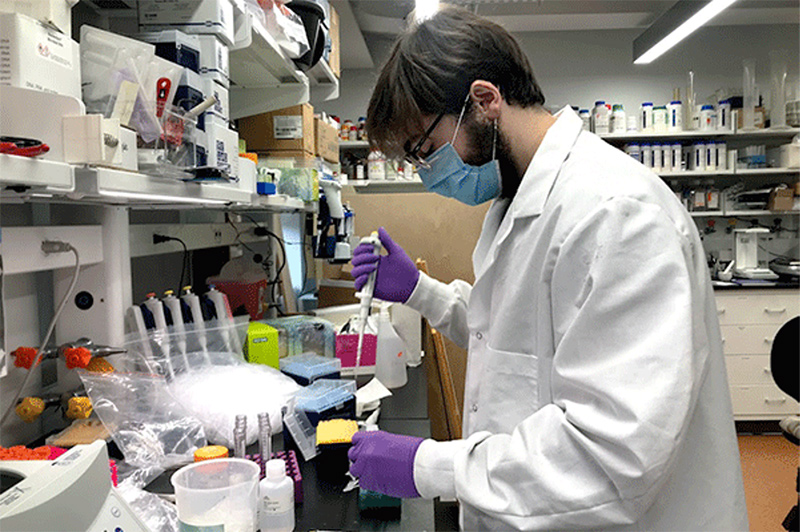

While the purification of nucleic acids from sludge is a known but difficult process, the logistics of doing so regularly and accurately at scale have few precedents. To find the best way forward, Annabelle Pan, Jordan Peccia, and Alessandro Zulli of Yale’s Environmental Engineering Program began a CDC-funded project. The goal? To actively monitor SARS-CoV-2 RNA levels from sludge samples taken from wastewater treatment facilities across the state of Connecticut.

In theory this would allow the team to detect community outbreaks as they began, giving public health officials the forewarning to take proper action. “Testing municipal wastewater provides similar information to randomly and anonymously testing thousands of people, but it's much cheaper,” explained Annabelle Pan. “For many places around the world, this may make wastewater monitoring a more realistic and affordable option than comprehensive testing programs.”

“Testing municipal wastewater provides similar information to randomly and anonymously testing thousands of people, but it's much cheaper.”

-Annabelle Pan

Research Technician, Yale School of Engineering & Applied Sciences

As expected, the initial push was a race to tie together a dozen loose ends. “The first month or so of this project was spent gathering samples, figuring out protocols, and ironing out all kinks.” said Alessandro Zulli. When everything finally came together, the results were anything but uncertain: “The first time we aggregated the data for New Haven and saw a curve that fit the cases to that point back in April was mind blowing.”

With now-validated methods, the team had to scale the initiative to the state level. Though the science was sound, the logistics involved were complex. “Sludge testing isn't super fancy science, but putting together all the pieces to make it work requires some coordination,” explained Pan. “You need people at a wastewater treatment plant who are willing to take samples for you, people who can transport those samples to a lab in a matter of hours, and people running extractions and PCR.”

“One daily primary sludge sample from the New Haven, CT wastewater treatment plant represents a population of 200,000 people.”

-Annabelle Pan

Research Technician, Yale Environmental Engineering Program

Each sample received was able to provide insight into high volumes of people: “One daily primary sludge sample from the New Haven, CT Wastewater Treatment Plant represents a population of 200,000 people,” said Pan. These results were made publicly available using a web reporting tool, so health officials and private individuals alike could use it to guide their actions.

But the tangle of local logistics was not the only challenge the team faced when trying to obtain and maintain these live results. Like many scientists, they were impacted by the supply chain shortages caused by the very pandemic they were trying to monitor. “We experienced a supply chain issue in October when the kit we originally used went out of stock indefinitely,” said Pan. “That was quite stressful because we had to scramble to find a replacement kit.”

Eventually the team found the Quick-RNA Fecal/Soil Microbe Microprep Kit suitable for their needs, “Getting a nice ~30,000ng of RNA out of the first extraction we did using the Zymo kit was truly uplifting and relieving,” said Pan. The kit enabled the team to process more samples at once, allowing the testing to be implemented with minimal resources while maximizing coverage. While making their process significantly more time efficient had a new benefit, as it allowed them to more easily comply with COVID era protocols and social distancing.

With their extraction kit and workflow validated, the team was able to begin state-wide monitoring. Helping control this global pandemic is a stressful task for any researcher, but the Yale team found gratitude in their role during difficult times. “It’s given me some purpose throughout this pandemic, and allowed me to contribute to efforts to stop the spread,” said Pan. “I’m glad for the chance to apply previously learned skills to a project this important.”

The availability of the data has also helped locals assess the best course of action, “My friends used this data to weigh being more cautious back in late October, when New Haven’s wastewater started to show a spike in covid RNA,” shared Pan.

Local public health officials have likewise used this data to take strategic action, meeting with the team twice a week. When RNA levels rose to concerning levels, the Mayor of Stamford implemented a robocall to advise residents on how to best avoid the virus.

This near-live aspect of the data is one of its most useful attributes for individuals and policymakers alike. “The value of this project has really been in providing real-time data that isn’t subject to the lags inherent to testing for cases, and for confirming/predicting trends in cases,” said Alessandro.

“The value of this project has really been in providing real-time data that isn’t subject to the lags inherent to testing for cases.”

-Alessandro Zulli

PhD Student, Yale Environmental Engineering Program

Of course, in the midst of this success the team has not forgotten that ever-present followup to successful science: repeatability. Would other universities be able to offer these services to the municipalities in which they reside? The team thinks so.

“I would say that most large institutions have the resources necessary to implement a program like this already,” said Alessandro. “It’s an incredible way to not only benefit their students, but the larger population surrounding the university.”

This project used the Quick-RNA Fecal/Soil Microbe Microprep Kit to extract viral RNA from sludge. Zymo Research has since upgraded and optimized viral RNA extraction from wastewater; the new Zymo Environ Water RNA Kit increases RNA yields from wastewater by 8-fold with its unique Water Concentrating Buffer. Zymo Research proudly provides a variety of solutions for environmental monitoring specially designed for organizations monitoring COVID-19 surges in wastewater.